LL #39 | Thriving in Complexity

Understanding Different States of the World, Change Management, and War

How to Thrive in Complexity

A tweet made the rounds this week offering a simple model for why change management is so difficult:

The model is simple. It feels good. And it’s the tip of a much bigger iceberg.

The iceberg is something profound that’s easy to miss—a set of traps that are common to fall into as a leader, and reliable principles that you can use to navigate them.

In her 2019 book Unlocking Leadership Mindtraps: How to Thrive in Complexity, Jennifer Garvey Berger discusses five common mental traps that limit leaders’ ability to effectively address complex challenges.

There are two which I’ve found to be particularly damning:

We are trapped by Simple Stories

We are trapped by our Need for Rightness

Relatable? Most definitely. Who doesn’t love simplicity and being right?

There’s nothing inherently wrong with simplicity or seeking the right answer. As leaders, communicating with simplicity and getting things right are essential skills.

The challenge arises when we seek simplicity and rightness too soon or in the wrong context. In particular, when we attempt to enact change on complex issues or in complex environments.

In these circumstances, successful change requires a multivariate approach. There is no single thing that makes the difference. We must focus and make progress on a number of different variables, simultaneously.

If any one is missing, we may miss the mark. But in novel complexity, we may not even know what those variables are!

This is why simple stories and rightness are traps.

If we optimize too much for simple stories, we may not see underlying complexity and miss key variables that must be addressed for us to be successful.

if we optimize for rightness, we may spend too long trying to think or analyze our way to the right solution, rather than experimenting to uncover the terrain and discover what the key variables are.

How do we escape the traps of simple stories and rightness to better address complexity?

Awareness is a great first step.

Jennifer Garvey Berger proposes three essential habits of mind in her 2015 book Simple Habits for Complex Times:

Ask Different Questions. The questions we ask ourselves create the reality that we see. By asking different questions we get more information about reality and evolve our mind.

If you often find yourself trapped by rightness, a good question to ask is How might I be wrong?Take Multiple Perspectives. No single person is capable of capturing the whole of reality by themself. The more we rely on only our own perspective, the narrower the picture we have and the less we are able to effectively adapt.

The solution is simple: take more perspectives.

Imagine you’re approaching the situation as an artist, an engineer, and an entrepreneur. What might they see? How might they act?

Imagine how different people that you know and respect might approach the problem. Gather those perspectives and really try to understand them. Why does this person think that way? What’s their goal? What’s motivating that?

The more perspectives you have, the more effectively you can see and navigate the complexity of a situation.See in Systems. Everything you interact with is embedded in a system. Any part of a system has a relationship to other parts of the system as well as the system as a whole.

If you change any part of a system, it affects other parts, which will in turn have effects that feedback to the initial part that you sought to change. The first effect is most commonly called a first order effect, while the effects of the effects are called second and third order effects.

One hallmark of complex systems is that second and third order effects tend to dwarf first order effects. Therefore if you don’t consider how a system will respond to your initial intervention, you’ll struggle to ever get the system, or any part of it, to the state that you’d like for it to be in.

The more you understand the systems that we live in, the more clearly you can see the second and third order effects of your actions. This understanding is a super power for effectively creating complex change.

The modern world is defined by complexity. By practicing these simple habits, you’re better able to meet the outer complexity that you face.

Cynefin: A Model for Understanding Complexity and Different States of the World

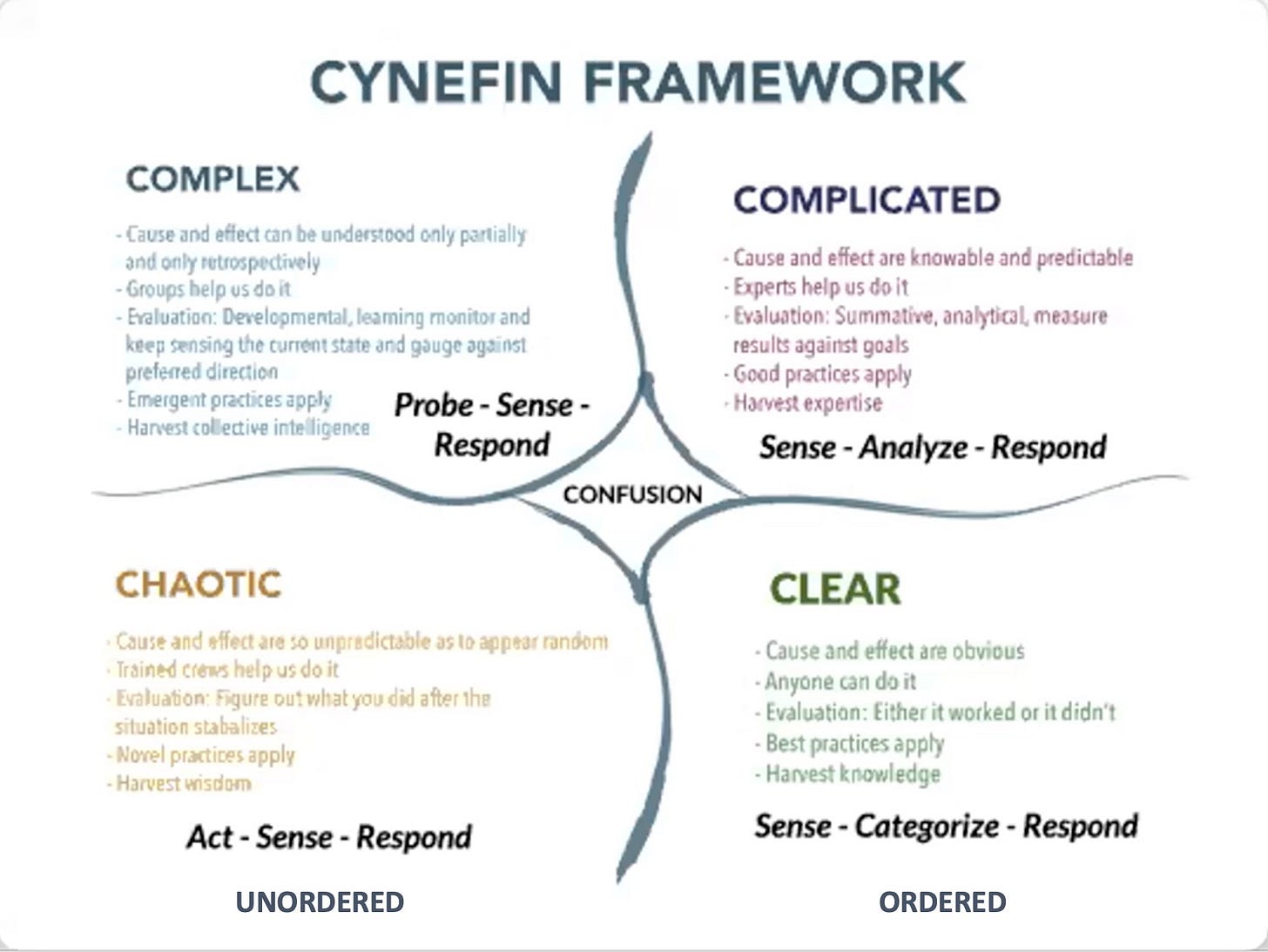

Cynefin is a framework created by Dave Snowden in 1999. It’s mean to to aid decision-making by understanding the environment one is in and describing how one should act based on that environment.

Cynefin describes five environments:

Clear. In clear environments, cause and effect are obvious. Anyone can solve problems. It’s obvious if problems are effectively solved or not. Here we should apply best practices: there is a clear best way to do things, and that is how we should do it.

Complicated. In complicated environments, cause and effect are knowable and predictable, but take some analysis to understand. It’s best to lean on experts with good practices here: there is no single best path, but many possible paths which trained experts will likely know. An example of this might be hiring an accountant to do your taxes.

Complex: In complex environments, cause and effect can only be partially understood and discerned after action has been taken. In complexity, experimentation and learning are essential. Emergent practices are best—we must discover what works. Leaning on collective intelligence (multiple perspectives) is an essential strategy. An example of this is introducing a new innovative technology to market.

Chaos: In chaotic environments, cause and effect is so unpredictable that it appears random. It is best to try novel practices and apply initial constraints rather than prescribe solutions. In these environments you can only really evaluate after things have settled. Think War (see below).

Confusion or Disorder: This is the space of not knowing which environment you’re in. The danger here is the tendency to blindly apply strategies from the environment you most commonly work in, even if those strategies are highly mismatched with the reality of your present environment.

Cynefin is a powerful starting point to think through how you’d like to tackle problems.

If you’re interested in learning more about Cynefin, watch it’s creator, Dave Snowden, discuss it here.

Practical Applications of Complexity Thinking & Cynefin

“There are five different environments and one of them is Chaos. And this is where all Ukrainians were in March when it was not clear what would happen, whether Kyiv would be captured by the Russian army or not.

I knew how to lead in complexity, according to the Cynefin framework. I should embrace uncertainty and shouldn’t worry about changing plans every 30 minutes. I just had to make small quick planning of the act and then act without waiting. And then sense the results of the act, get feedback, become smarter, and do another activity. And so on.

In contrast, my colleagues in similar positions in the Ukrainian army told me that they worry that they cannot communicate plans and other things. They spent a lot of energy and were nervous about it. I tried to help them by explaining that they simply shouldn’t worry about plans being ruined, that this is a norm in the Chaos domain. Sometimes they listened to my advice and felt much better.”

Dmytro found that many of his fellow officers were burning emotional energy worrying about the constant state of change that they and their colleagues were in.

Dmytro’s experience was different.

When he identified the Cynefin environment he was in, he aligned his expectations to what was normal for that environment. He knew that not only would plans constantly change, but that they should change to address the complexity that was unfolding.

This alignment of expectations reduced stress for him and his colleagues. Rather than worrying about the constant change, they embraced it. This allowed them to channel that time and energy into effective action.

“If you are in the Chaos domain there are no best practices as your context changes. So if something worked before there is simply no guarantee that it will work again or in your dynamically changing environment. So you should be really careful when someone insists on best practices. This helped me to calmly ignore suggestions that I felt would not work. And instead of an imaginary “silver bullet”, act and create new practices.”

In Chaos, the uncertainty is so extreme that an orientation to what’s historically worked is actually detrimental.

No chaotic situation is ever the same, and so what worked before is actually unlikely to work now. The only effective path forward is to invent new approaches.

In both of these situations, a commitment to best practices or even a consistent strategy would have been devastating.

This is the power of Cynefin: by understanding the properties of the environment that you’re in, you are empowered to act most effectively.

Read: From agile coach to the military officer: breaking stereotypes about leadership in the army

Questions

Where are you blind to complexity in your life and work?

In what contexts are you most often trapped by simple stories and the need to be right?

To cultivate the habit of asking different questions:

What are the questions that you commonly bring to your life and work?

How do those questions create the world you see?

How could shifting your questions shift your mind? Your perception of reality?

To cultivate the habit of taking multiple perspectives:

How many perspectives can I hold?

When are you unable to hold different perspectives?

What happens to your ability to hold different perspectives when in conflict?

To cultivate the habit of seeing in systems:

How do you think about cause and effect?

What patterns can you see? What are the outliers?

How do you hold and manage the polarity between the patterns and the outliers?

What are the different environments of your life? Which environments is your approach out of sync with?